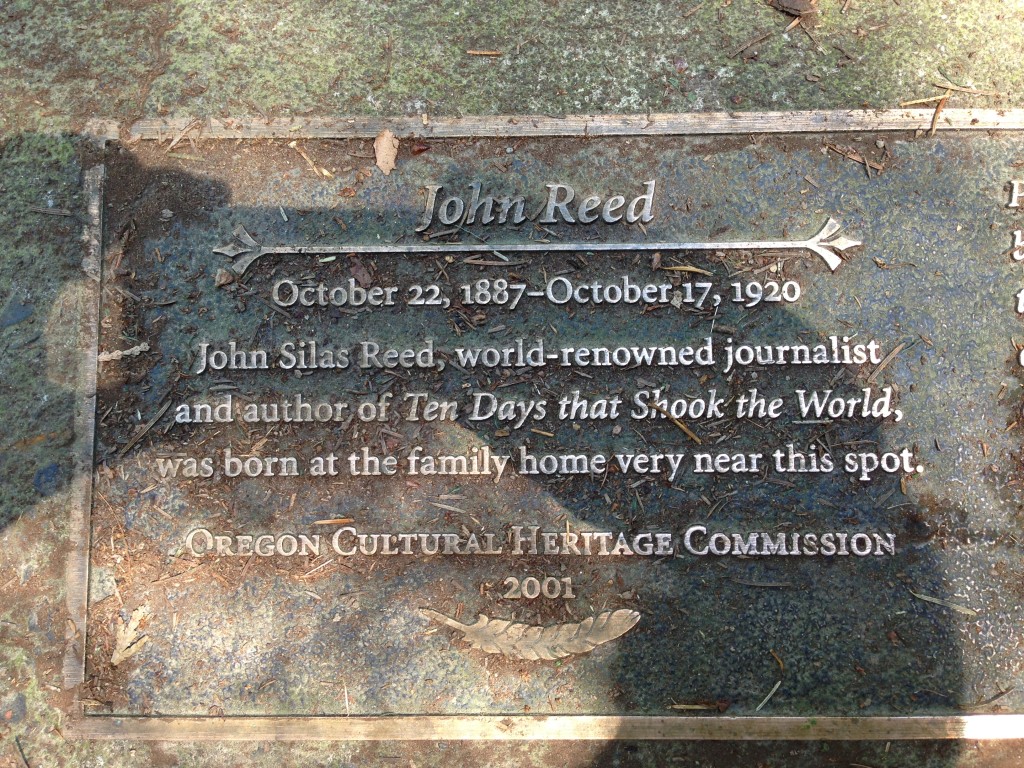

John Reed

A Taste of Justice

Published: The Masses, April, 1913 | via John Reed Internet Archive

As soon as the dark sets in, young girls begin to pass that Corner—squat figured, hard-faced “cheap” girls, like dusty little birds wrapped too tightly in their feathers. They come up Irving Place from Fourteenth Street, turn back toward Union Square on Sixteenth, stroll down Fifteenth (passing the Corner again) to Third Avenue, and so around—always drawn back to the Corner. By some mysterious magnetism, the Corner of Fifteenth Street and Irving Place fascinates them. Perhaps that particular spot means Adventure, or Fortune, or even Love. How did it come to have such significance? The men know that this is so; at night each shadow in the vicinity contains its derby hat, and a few bold spirits even stand in the full glare of the are-light. Brushing against them, luring with their swaying hips, whispering from immovable lips the shocking little intimacies that Business has borrowed from Love, the girls pass.

The place has its inevitable Cop. He follows the same general beat as the girls do, but at a slower, more majestic pace. It is his job to pretend that no such thing exists. This he does by keeping the girls perpetually walking—to create the illusion that they’re going somewhere. Society allows vice no rest. If women stood still, what would become of us all? When the Cop appears on the Corner, the women who are lingering there scatter like a shoal of fish; and until he moves on, they wait in the dark side streets. Suppose he caught one? “The Island for her! That’s the place they cut off girls’ hair!” But the policeman is a good sport. He employs no treachery, simply stands a moment, proudly twirling his club, and then moves down toward Fourteenth Street. It gives him an immense satisfaction to see the girls scatter.

His broad back retreats in the gloom, and the girls return—crossing and recrossing, passing and repassing with tireless feet.

Standing on that Corner, watching the little comedy, my ears were full of low whisperings and the soft scuff of their feet. They cursed at me, or guyed me, according to whether or not they had had any dinner. And then came the Cop.

His ponderous shoulders came rolling out of the gloom of Fifteenth Street, with the satisfied arrogance of an absolute monarch. Soundlessly the girls vanished, and the Corner contained but three living things: the hissing arc-light, the Cop, and myself.

He stood for a moment, juggling his club, and peering sullenly around. He seemed discontented about something; perhaps his conscience was troubling him. Then his eye fell on me, and he frowned.

“Move on!” he ordered, with an imperial jerk of the head.

“Why?” I asked.

“Never mind why. Because I say so. Come on now.” He moved slowly in my direction.

“I’m doing nothing,” said I. “I know of no law that prevents a citizen from standing on the corner, so long as he doesn’t hold up traffic.”

“Chop it!” rumbled the Cop, waving his club suggestively at me, “Now git along, or I’ll fan ye !”

I perceived a middle-aged man hurrying along with a bundle under his arm.

“Hold on,” I said; and then to the stranger, “I beg your pardon, but would you mind witnessing this business?”

“Sure,” he remarked cheerfully. “What’s the row?”

“I was standing inoffensively on this corner, when this officer ordered me to move on. I don’t see why I should move on. He says he’ll beat me with his club if I don’t. Now, I want you to witness that I am making no resistance. If I’ve been doing anything wrong, I demand that I be arrested and taken to the Night Court.” The Cop removed his helmet and scratched his head dubiously.

“That sounds reasonable.” The stranger grinned. “Want my name?”

But the Cop saw the grin. “Come on then,” he growled, taking me roughly by the arm. The stranger bade us good-night and departed, still grinning. The Cop and I went up Fifteenth Street, neither of us saying anything. I could see that he was troubled and considered letting me go. But he gritted his teeth and stubbornly proceeded.

We entered the dingy respectability of the Night Court, passed through a side corridor, and came to the door that gives onto the railed space where criminals stand before the Bench. The door was open, and I could see beyond the bar a thin scattering of people of the benches—sightseers, the morbidly curious, an old Jewess with a brown wig, waiting, waiting, with her eyes fixed upon the door through which prisoners appear. There were the usual few lights high in the lofty ceiling, the ugly, dark panelling of imitation mahogany that is meant to impress, and only succeeds in casting a gloom. It seems that Justice must always shun the light.

There was another prisoner before me, a slight, girlish figure that did not reach the shoulder of the policeman who held her arm. Her skirt was wrinkled and indiscriminate, and hung too closely about her hips; her shoes were cracked and too large; an enormous limp willow plume topped her off. The Judge lifted a black-robed arm—I could not hear what he said.

“Soliciting,” said the hoarse voice of the policeman, “Sixth Avenue near Twenty-third—-”

“Ten days on the Island—next case!”

The girl threw back her head and laughed insolently.

“You —” she shrilled, and laughed again. But the Cop thrust her violently before him, and they passed out at the other door.

And I went forward with her laughter still sounding in my ears.

The Judge was writing something on a piece of paper. Without looking up he snapped:

“What’s the charge, officer?”

“Resisting an officer,” said the Cop surlily. “I told him to move on an’ he says he wouldn’t—”

“Hum,” murmured the Judge abstractedly, still writing. “Wouldn’t, eh? Well, what have you got to say for yourself?”

I did not answer.

“Won’t talk, eh ? Well, I guess you get——”

Then he looked up, nodded, and smiled.

“Hello, Reed!” he said. He venomously regarded the Cop. “Next time you pull a friend of mine—” suggestively, he left the threat unfinished. Then to me, “Want to sit up on the Bench for a while?”

Transcribed: Sally Ryan for marxists.org in 2000

The movie Reds is about John Reed:

[amazon asin=B000GG4Y32&template=iframe image]

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts